The role of the MP

The constituency link – and why PR would strengthen it

LCER believes that any system of PR which is introduced in the UK should retain the link between members of the House of Commons and their constituents. The constituency link is valued by voters and MPs alike, and systems such as the Additional Member System (AMS) or the Single Transferable Vote (STV) would retain local representation, while putting an end to the scandal of millions of wasted votes that we see under First Past the Post.

But rather than just retaining the constituency link, I believe a PR system would substantially enhance the relationship between MPs and their voters. In this post, I’ll look at the different roles which MPs fulfil, and how PR could help MPs work more effectively in all of those roles.

What does an MP do?

Members of Parliament elected to the House of Commons have officially got three main roles.

Firstly, and by far the most significantly, MPs support, through their membership of a political party, the appointment of a government that controls not just the laws that are passed but the regulations that are used and the budget that is required to implement those laws and regulations. The most significant thing any MP can do is to vote for – or against – a motion of no-confidence in the government. By turning up at the start of the parliamentary term, MPs signal that there are enough of them to ensure that their Party’s choice of Prime Minister will have a majority in the House of Commons. By turning up at subsequent votes they indicate that a vote of no-confidence will not succeed. For this purpose, no effort or intelligence is required – just loyalty to the Party and the ability to get through the voting lobby. Admittedly, leading members of a political party can influence or even determine their Party’s policies, but the number of MPs who create policy is surprisingly small, and often advisors in the Leader’s office have more influence than junior ministers or even Cabinet ministers. Clearly, while MPs are important in themselves, the voters’ instincts to vote primarily for a government to run the country are perfectly sensible. An electoral system such as FPTP, which respects the constituency link but which does not respect the wishes of the majority of voters as to who should be in government, is not doing its primary job.

Secondly, Members of Parliament can take up casework on behalf of their constituents, and can champion such cases in Parliament. This is important as it provides a link between policy and the lived experience of citizens. It is all too easy for a government, or officials, to claim that a policy does not adversely impact anyone. Such denials cannot withstand a specific case raised in Parliament by an MP showing that, for instance, one of her constituents has lost his job and his home because he cannot prove his citizenship, despite having lived and worked in the UK for 50 years. Keeping the constituency link gives an MP individual constituents to respond to. However, voters have increasingly found themselves being ignored by MPs who do not share their political views. Having additional members under AMS, or a multi-member constituency under STV, would ensure that the vast majority of voters had an MP that they could trust.

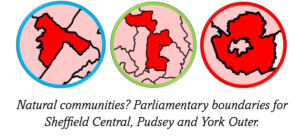

The third role is to act as a champion for their constituency as a whole. The main justification for electing MPs on the basis of a geographic constituency is to provide an elected person in the House of Commons who can speak up for the needs of a particular geographic community. Unfortunately, in the interest of making the constituencies the same size, the boundaries of Parliamentary Constituencies have become more and more arbitrary, and are about to become even more so, as the latest round of boundary revisions is based on an even smaller margin of numerical difference. I was lucky as MP for Ipswich – I had one Borough Council to work with, and although my constituency didn’t cover the whole Borough, it covered the majority. I was able to interact as the local MP with the Chamber of Commerce, the Business Improvement District, the CAB, the DWP, the Police and any number of other Borough-wide organisations. Most of the UK’s parliamentary constituencies force local authorities to work with two or more MPs, and many force MPs to work with two or more local authorities. In this case, the role of MP as place champion is made very much more difficult and less effective.

The MP’s electoral role

Another role exists, which is unofficial, but which is often uppermost in the MP’s mind – to act as an electoral champion for their political party. Democracy is meant to be about holding governments, parties and MPs to account. As a human being rather than an institution, an MP ought to be able to epitomise by their actions and attitudes within their constituency the principles of their party, and thus help increase (or reduce!) the vote for their party at the next General Election. However, because under FPTP constituency boundaries are based not on natural communities but simply on the number of citizens living within an arbitrarily drawn line, many voters do not know either which parliamentary constituency they live in, nor who their MP is. Clearly, a significant proportion of voters cannot possibly be voting for a local MP they know and trust – in those cases the electoral champion role clearly doesn’t function at all.

How PR can enhance the constituency link

MPs need to represent meaningful geographic constituencies, on boundaries which the voters recognise, and which do not frequently change. In addition, parliamentary constituency boundaries should, wherever possible, be coterminous with local authority boundaries, to enable the local community to develop the most effective relationship with their MP or MPs. To achieve that under a single-member constituency system will involve a significant level of divergence in the size of the electorate in each constituency. Under FPTP, such a level of divergence would risk making the discrepancy between the percentage of votes cast nationwide and the number of seats allocated to each party even wider than at present. With an STV electoral system, that divergence in size can be accommodated by having fewer or more MPs in each multi-member constituency. With an AMS system, that divergence can be more accurately compensated for by electing top-up members on a regional or sub-regional basis. Either way, a PR system has the potential to enable the redrawing of constituencies so that they share their boundaries with local authorities, are easily identifiable, remain the same for generations and not just for a few years, provide most voters with an MP that they can trust, AND still return a government which far more closely matches the proportion of votes cast across the country. In short, PR won’t just retain the link between MPs and constituents, it will make it work a whole lot better.